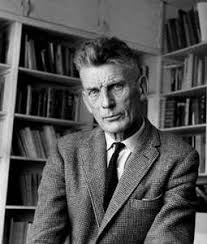

Samuel Beckett was born on 13 April 1906 in Foxrock, near Dublin, into a family of the Irish Protestant bourgeoisie. He began his studies at Earlsfort House, a Protestant school in Dublin run by a Frenchman, where, at a very young age, he discovered the French language, the start of a lifelong interest. At the age of 14 he was sent to the Anglo-Irish Portora Royal School, in Enniskillen, where Oscar Wilde had once been a pupil. Between 1923 and 1927, Beckett studied French, English and Italian at Trinity College Dublin, laying the foundations for the culture that would make him one of the most erudite writers of the 20th century. He had a particular affinity with the work of Dante.

Having obtained his Bachelor of Arts degree, Beckett was appointed lecturer at the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris. It was in Paris that he met James Joyce, becoming assistant and friend to this revered figure. During his two-year stay, Beckett also launched his own writing career with the long poem, Whoroscope, half serious, half comical. His return to Dublin in 1930 as a lecturer at Trinity College marked the beginning of a period of instability: his teaching duties gave him no satisfaction, he failed to reintegrate into Irish society, and he soon resigned his post. The death of his father in 1933 provided him with some financial resources, and Beckett soon travelled back to Continental Europe, including Germany. Returning to Paris in 1937, he decided to settle there permanently, taking a small apartment on the Rue des Favorites in the 15th arrondissement, near Montparnasse. Around this time, he suffered a near-fatal assault, when he was stabbed in the street, for no reason, by a pimp, an absurd event that marked him deeply. Beckett’s first novel, Murphy (1938), was well received in the English press. The outbreak of the Second World War surprised him in Ireland during a visit to his mother. Having made his way back to Paris, he refused the advantage of his Irish nationality, which would have ensured him neutral status, and instead joined the French Resistance, becoming a member of the Franco-English Gloria network. Warned of a betrayal, he narrowly escaped arrest, fleeing with his partner Suzanne. They took refuge in the Vaucluse, in Roussillon, with the Bonnelly family. Berthe Bonnelly, who had been left alone with her young son Aimé following her husband’s arrest by the Germans, welcomed them on her farm, where Beckett worked as an agricultural labourer and helped with the harvest. This period is of crucial importance in Beckett’s life and for his work. In Roussillon, he discovered the rural world, hunger, fear and waiting… It was in Roussillon that he decided to make French his preferred literary language. And it was in Roussillon that he first conceived the subject of the play that would make him famous, Waiting for Godot, a masterpiece of the theatre of the absurd, written in 1948. Indeed, Beckett explicitly alludes to his life as a farm worker in the script.

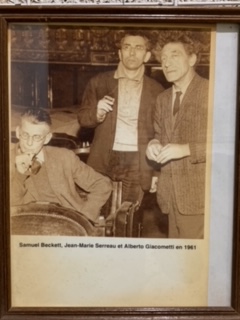

On 30 March 1945, Beckett was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Médaille de la Résistance. Living in Paris once more, detached from his native Ireland and his mother tongue alike, he now became a French author, using his adopted language for both fiction and drama, resuming composition in English only for rare exceptions and in order to translate his own work. In the postwar years, despite difficult material conditions, driven by the certainty of his vocation, he experienced a veritable writing frenzy. Works accumulated. It was Suzanne who managed to find Beckett a publisher, Jérôme Lindon, at the Editions de Minuit, for the trilogy of novels Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnameable. In 1953, thanks to Suzanne’s efforts, the French actor and director Roger Blin finally staged Waiting for Godot, which became a theatrical sensation, triggering heated responses for and against, and making Beckett’s name. From then on, theatre took a new place in his life, not only as an author, but also as a director of his own plays. He wrote Endgame in 1954, Krapp’s Last Tape in 1958 and Happy Days in 1960. He also composed a movie script, entitled simply Film.

Beckett’s works express anguish in the face of the absurdity of the human condition, nothingness, and the impossibility of communication. The passage of time typically reduces his characters to immobility; all they can do is fill their time with words – words that echo away in futility. However, this pessimism does not exclude a certain humour and a huge feat of derision. Over time, Beckett came to treat his themes in an increasingly lapidary manner, employing a language that was more and more concise and dry.

As his fame continued to grow, Beckett found himself in great demand. In 1969, he received the Nobel Prize for Literature “for his writing, which – in new forms for the novel and drama – in the destitution of modern man acquires its elevation.” For Beckett, being awarded this honour was a disaster, as it further increased his fame and fuelled academic interest in his work. With irksome fame came irksome responsibilities. Nevertheless, his publisher, Jérôme Lindon, travelled to Stockholm to collect the prize on behalf of the author.

Beckett’s final years were marked by a need for solitude, and his literary output reflects this personal situation. In Ill Seen, Ill Said and A Piece of Monologue, his style becomes more and more minimalistic. Worstward Ho, his penultimate text, is a cry of suffering, an expression of incredible distress, where language is stripped down, reduced to the extreme and pushed to the very brink of silence. This piece, written in English, was never translated by the writer, because he feared being plunged back into its torment. Suzanne Beckett passed away on 17 July 1989, and Samuel Beckett died on 22 December the same year. They are buried in the Montparnasse cemetery in Paris.